Growing up, it all seems so one-sided

Opinions all provided

The future pre-decided

Detached and subdivided

In the mass-production zone

Nowhere is the dreamer

Or the misfit so alone

It’s been a year since we lost Neal Peart, the extraordinary drummer, lyricist, and writer, and it’s hard to reconcile those feelings, but those lines above have always broken my heart.

They’re from the song “Subdivisions,” from the album of the same name, and I wasn’t even a fan of that album at the time. That’s because I was sixteen, and it had made the unforgivable mistake of being played on the radio. Rush was supposed to be my band, for kids like me who didn’t listen to pop radio, because that music was popular. I was a misfit, an outcast, one of the self-exiled, just as my favorite band was self-exiled, purposefully devoted to musical integrity as they defined it, indifferent to the mass collective.

Like the band I admired, I was drawn to the less traveled path, and instinctively spurned the pretensions of the mainstream. I didn’t have the words to ground this concept in a tangible way, not yet anyway. It was Rush — through Neil Peart — that gave them to me. They did that by exemplifying an ongoing commitment to integrity, to making the music they loved, and screw the label — or the radio — if they didn’t get it.

And apparently they didn’t. They used to play Spirit of the Radio on the FM stations too, oblivious to the sharp critique aimed directly at them at the heart of the song:

One likes to believe

In the freedom of music

But glittering prizes

And endless compromises

Shatter the illusion

Of integrity

But let me go back a bit. When I discovered Rush in high school, music was about to become my salvation. Before that, I’d been a crazy-shy kid. I had few friends. I wouldn’t start to grow until my sophomore year, and then I almost didn’t stop, but until then, I was always the smallest in class. I was uselessly incapable of performing all the things that seemed to matter so much in the subdivided realm of grammar school. I dropped every ball that had the misfortune of being hit in my direction. I could not do a pull-up if my life depended on it.

Worse yet, I’d been tagged as a loser in sixth grade, the year my family fell apart, and the business crashed, and I got kicked out of advanced English for refusing to read The Chronicles of Narnia — just, because. I can remember, as if it were this morning, the time the prettiest and cruelest girl in school stopped me in the hall, looked me up and down, and said through her gum, “Um, like where do you get your clothes?”

Fast forward to the fall of 1981. High school. And while doing homework one day – or maybe ignoring it – out of the radio came an electrifying guitar riff followed by a rumble of drums that seemed to detonate from the speakers. What was this thing that I’d found? I grabbed the pillows from the living room couch, dug out a pair of sticks I’d gotten as a kid, and I tried to play along to “Limelight” (as if).

A couple days later I noticed a kid at school with a Rush t-shirt. I asked him about the song I couldn’t stop thinking about.

“Oh yeah?” he said. “You like that, I got an album for you.”

Next day, he reached into his book bag, and it’s just a dream, but in my remembrance, there was a parting of the clouds and a chorus of angels as he handed over a well-thumbed 2112.

“And you’re gonna wanna use headphones.”

I took that album home, dropped the needle, and with the first notes, it was love.

That’s my story. I bet if you’re reading this, yours is similar. From 2112, I went on to discover all the rest: Hemispheres and Caress of Steel and Permanent Waves and A Farewell to Kings, all the masterpieces of the band’s early ’70s days — and not just Rush, but the creative and, dare I say it, intellectual music of that album-oriented era. And I’d grow my hair, fumble around a drum kit (I still can’t play Limelight), make a bunch of friends, and find a community — an identity. The foundation was always music, our tastes grounded in the subculture, because our music wasn’t sappy and over-saturated with hooks and immediacy. It took effort. It wasn’t for the masses.

It belonged to me. To us. The outsiders. The misfits.

And while I never gave schoolbooks much attention, a Rush album was a literary experience. Yes, the music was spectacular, with performances elevated to super-human capacity — but it was the words that resonated just as much:

Each of us

A cell of awareness

Imperfect and incomplete

Genetic blends

With uncertain ends

On a fortune hunt

That’s far too fleet

These were lyrical puzzles, challenging but accessible. I was fifteen and learning to untangle verbal complexity. To think. And to explore, because from the back of the albums, I tracked down the references: Anthem, The Fountainhead and Kubla Khan, which led to Wordsworth, Shelly, Ginsburg, then Kerouac, Coltrane and Bird — a chain of artistic exploration that widened from music to…everything else. I had no idea at the time, but Neil Peart was my initiation into a love of intellectual discovery, without parents or teachers deciding what was appropriate or necessary — two of the ugliest words to describe the pursuit of knowledge — not as a means to an end, but for the pure joy of exercising the mind.

Obviously, I never met the man. And he’d be appalled at all this gushing and I wouldn’t have the guts — or the gall — to show it. You don’t have to read past these lines to understand how this modest and authentic man spurned celebrity:

Living in a fish-eye lens

caught in the camera eye

I have no heart to lie

I can’t pretend a stranger is a long-awaited friend

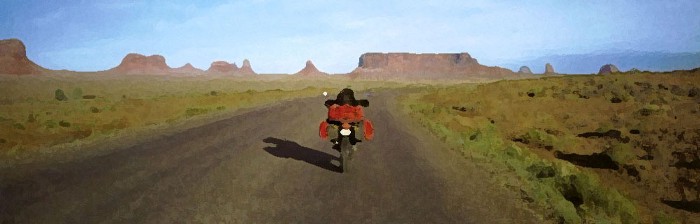

But I do have a secret fantasy. It goes like this. I’m out on my own Healing Road, just “following my front wheel” as Neil once wrote, trying to make sense of this brief and bewildering experience we call being. Pulling into a roadside diner, there’s a BMW GS propped under a tree, and beside it, on a bench, face in a book, sits this handsome and rugged dude with a skull cap and a contemplative curiosity across his face. I take in the scene. And leave him alone. Because I know better. Instead, I wait inside until he gets up to pay, and that’s when I sneak out to leave this note across the cylinders of the Ghost Rider’s machine:

Neil,

Just wanted to say: Thanks.

For everything.

– A long-awaited friend